The Three Forms of Efficiency and What They Mean for Investors

In the previous article, we explored the origins of the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH), from Jules Regnault’s early insights to Eugene Fama’s formalization of the theory in the 1960s and 70s.

Now it’s time to get practical. (There is also an older post from me about it).

Let’s dig into the three forms of market efficiency that Fama proposed — and why understanding them changes how you approach investing, from technical analysis to insider trading.

🧩 The Three Forms of Market Efficiency

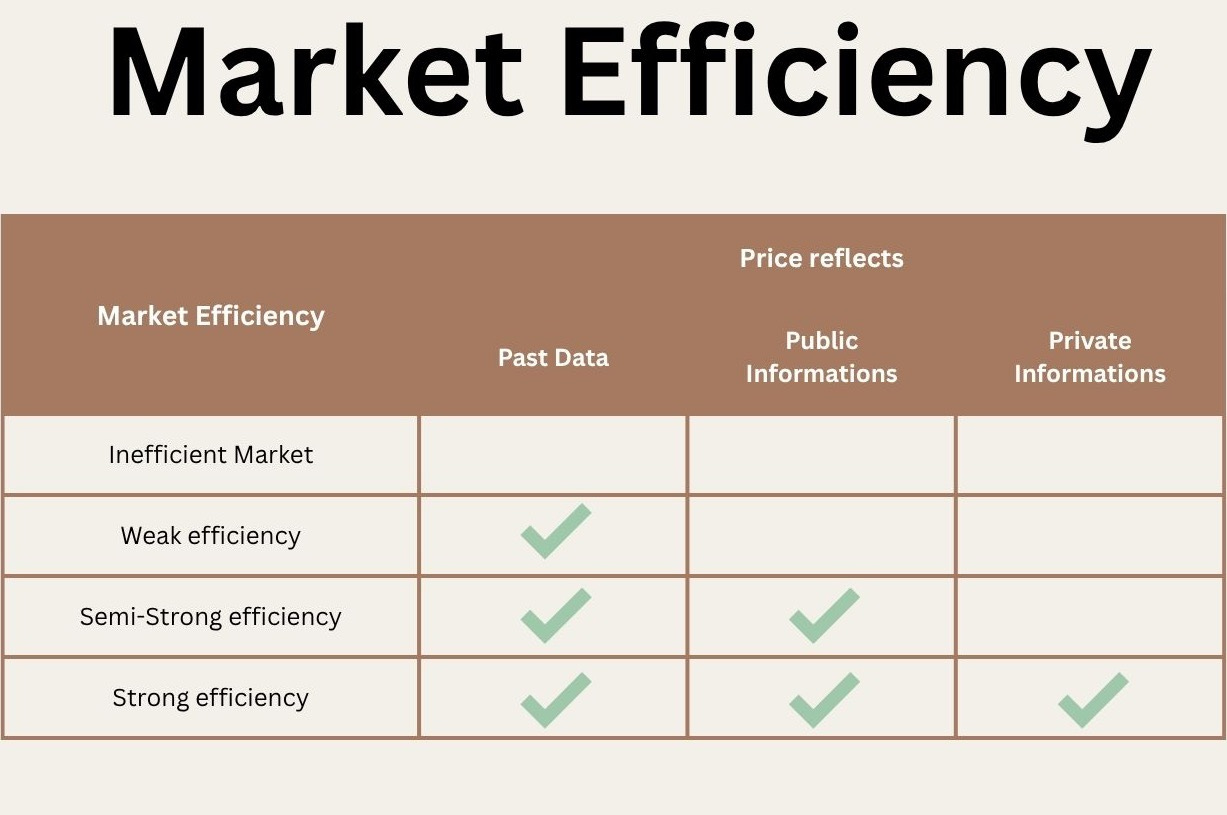

Fama’s classification is elegant and intuitive. He breaks down market efficiency into three levels, depending on the type of information reflected in prices.

Market Efficiency FormPrices Reflect...Can You Beat the Market?

Weak FormPast prices❌ Technical analysis

Semi-Strong FormPublic info❌ Fundamental analysis

Strong FormAll info (incl. private)❌ Nobody, not even insiders

Let’s break each one down.

1️⃣ Weak-Form Efficiency

Prices reflect all past price and volume data.

Implication:

You cannot beat the market by analyzing historical prices or chart patterns. In other words, technical analysis is uselessin an efficient market.

Example:

If a stock gained 10% last week, that tells you nothing about what it will do next week. Price changes are random, like coin tosses.

Even if short-term momentum or trends exist, they vanish quickly and can’t be exploited profitably after costs.

2️⃣ Semi-Strong Form Efficiency

Prices reflect all publicly available information.

This includes:

Company financial statements

Earnings reports

Macroeconomic data

Analyst forecasts

News headlines

Implication:

Fundamental analysis doesn’t help, because any insight you might extract from public information is already priced in.

Example:

If a company announces record-breaking earnings, the stock price already adjusts instantly, making it impossible to profit from the news unless you had the information before everyone else.

So if you’re building complex discounted cash flow (DCF) models hoping to find “undervalued gems,” be aware: in a semi-strong efficient market, everyone else has already done the same math.

3️⃣ Strong-Form Efficiency

Prices reflect all information — including private, insider knowledge.

If this form held in reality, then:

Even CEOs and insiders couldn’t beat the market.

Insider trading would be pointless.

Markets would be perfectly rational and unbeatable.

But let’s be honest — this is more of a theoretical extreme. Most researchers (and regulators) agree that strong-form efficiency does not hold in practice.

📉 What About Intrinsic Value?

The EMH assumes that there is such a thing as a “true” value for every asset — the present value of all future cash flows.

In an efficient market:

The market price should always equal the intrinsic value.

Simple in theory. But in practice?

Some economists argue that no intrinsic value truly exists — prices are simply what buyers and sellers agree on.

The idea of a “correct” or “fair” value is more of a theoretical construct than a measurable reality.

⚠️ The Efficiency Paradox

There’s a fascinating paradox at the heart of EMH:

If everyone believed markets were perfectly efficient, nobody would analyze data or look for mispricings.

But without those analysts, markets would become inefficient.

This is known as the Grossman-Stiglitz paradox — perfect efficiency is impossible because information has a cost. If nobody is incentivized to acquire it, prices won’t reflect it.

So... Are Markets Efficient?

The truth is — it depends.

Developed markets (like the U.S. or Europe) tend to be more efficient.

Emerging markets often show greater inefficiencies — due to lower liquidity, less regulation, and slower information flow.

Even in developed markets, short-term inefficiencies do arise — but they’re typically small, brief, and hard to exploit after costs.

TL;DR — Key Takeaways

Weak-form efficiency invalidates technical analysis.

Semi-strong efficiency challenges the usefulness of fundamental analysis.

Strong-form efficiency is mostly unrealistic — insider information still matters.

Markets may not be perfectly efficient, but they’re efficient enough that most people can’t beat them consistently.

For most investors, low-cost passive investing remains the rational choice.

In the next and final article of the series, we’ll look at:

Empirical evidence supporting or challenging EMH

Common market anomalies (like the January effect and momentum)

What all this means for your investment strategy

👉 Stay tuned: we’ll separate the real inefficiencies from the mirages.